Few genres have enjoyed such longevity of popularity as crime fiction over the last two centuries. The earliest detective story is generally considered to be Edgar Allan Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue (1841), which appeared in an edition of Graham’s Magazine and is credited as inspiring some of literature’s greatest detectives, including Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot.

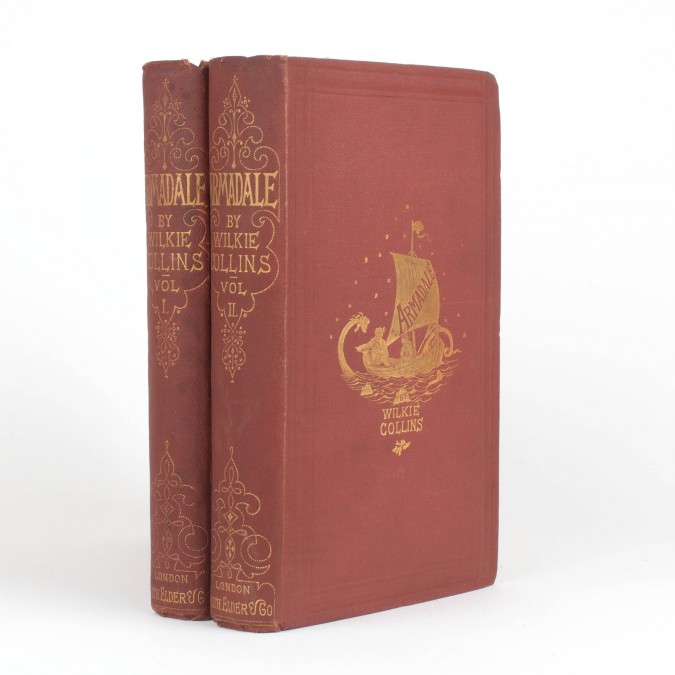

The success of Poe’s story led to others taking up his mantle and pushing the idea of the whodunnit further. One of the most important of these authors was Wilkie Collins, close friend of Charles Dickens and arguable father of the psychological thriller. His great works, including The Woman in White (1860) and Armadale (1866), centre around mysterious crimes and feature elements of the supernatural, but did not feature a detective in the mould of Poe’s Dupin.

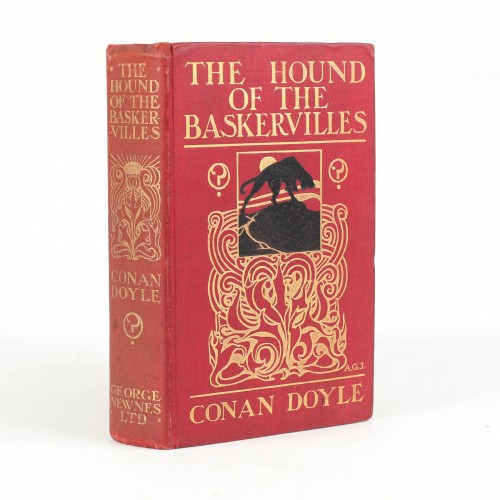

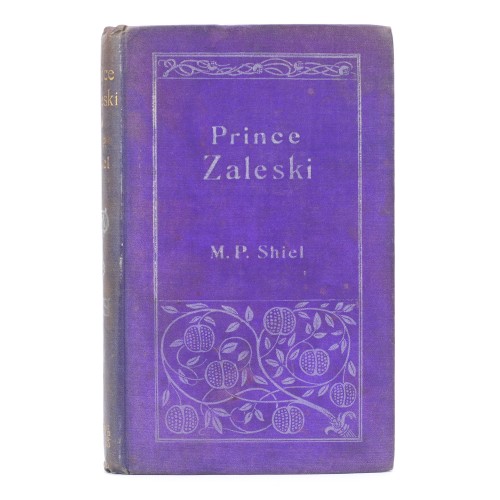

Although Collins' work often revolved around a crime, and featured an early example of the archetypical eccentric detective in Sergeant Cuff, he did not create a character who could be seen to be a natural successor to Dupin. However, the influence of Poe’s logician became ever clearer, with his creation cited as a direct influence on characters including Shiel’s opium-smoking exiled Russian Prince Zaleski, and, of course, Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes.

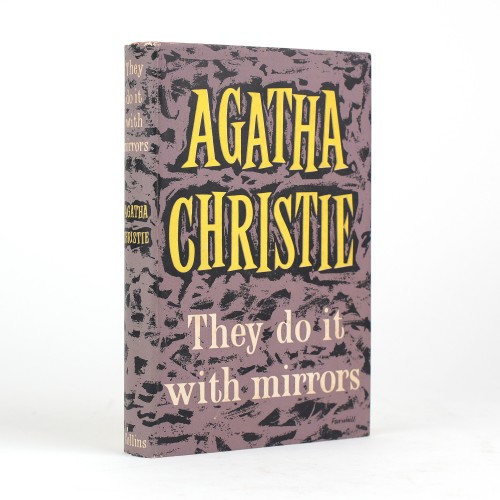

Although the 19th century was when crime fiction gathered steam, it was the period after the First World War when it entered its Golden Age. Connected to the earlier period by the continued publication of Holmes stories, the 1920s and 30s saw a proliferation of new writers emerging as powerhouses of crime fiction. These included the four ‘Queens of Crime’: Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham, and Ngaio Marsh, as well as household names such as G.K. Chesterton and Nicholas Blake. The novels of the Golden Age tended to feature mysteries that were solved by aloof, logical detectives who would rarely get their hands dirty - very much the precursor to today’s Cosy Crime movement.

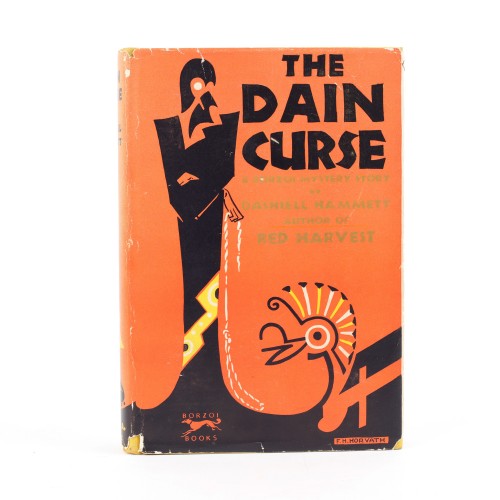

On the other side of the Atlantic, though, crime fiction was moving far from the country houses and upper classes of Britain’s offerings. Writers such as Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler began writing ‘Hardboiled’ novels; grittier detective stories with greater emphasis on realism and private investigators who would get embroiled in the depths of the crime world rather than deducing from the comfort of their chaise longue.

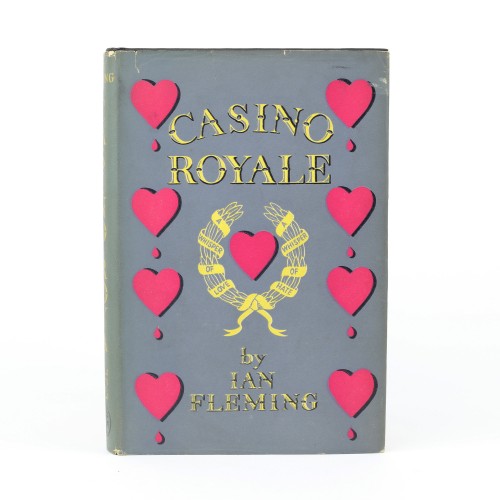

Simultaneously, a new form of crime fiction was emerging, led by British authors, but incorporating many of the features of Hardboiled crime, generally tending towards more violence and realism than pipes and puzzles: spy fiction. Early examples of this genre came from major authors such as Joseph Conrad’s Under Western Eyes (1911) and W. Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden (1928) and had a huge influence on later spy fiction greats, inspiring not only eminent writers such as Eric Ambler and John Le Carré, but also spy fiction’s greatest character James Bond, who first appeared in Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale (1953).

Bond, Holmes, Dupin and Poirot have all made the leap to TV and film, and the relationship between literary detectives and their on-screen iterations has gone from strength to strength, from Johnathan Gash’s antiques-dealing Lovejoy to Craig Russell’s British-German detective Jan Fabel, and shows no sign of slowing down.

Recent Posts

- The Evolution of Crime

- Tour The Bookshop On Your Screen

- The Genesis of Mr. Toad: A Short Publication History of The Wind In The Willows

- Frank Hurley's 'South'

- The "Other" Florence Harrison

- Picturing Enid Blyton

- Advent Calendar of Illustration 2020

- Depicting Jeeves and Wooster

- Evelyn Waugh Reviews Nancy Mitford

- The Envelope Booklets of T.N. Foulis

- "To Die Like English Gentlemen"

- Kay Nielsen's Fantasy World

- A Brief Look at Woodcut Illustration

- The Wealth Of Nations by Adam Smith

- What Big Stories You Have: Brothers Grimm

- Shackleton's Antarctic Career

- Inspiring Errol Le Cain's Fantasy Artwork

- Charlie & The Great Glass Elevator

- Firsts London - An Audio Tour Of Our Booth

- Jessie M. King's Poetic Art, Books & Jewellery

Blog Archive

- January 2024 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- August 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (1)

- July 2020 (2)

- March 2020 (3)

- February 2020 (2)

- October 2019 (2)

- July 2019 (2)

- May 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (2)

- February 2019 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- November 2018 (1)

- October 2018 (2)