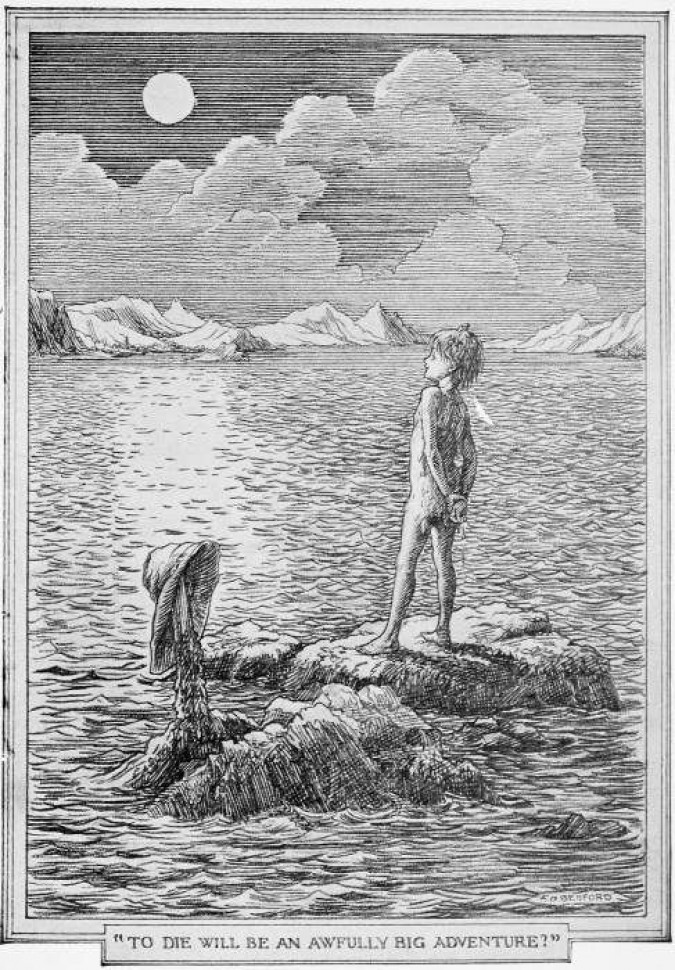

About halfway through J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, both in the 1904 play and in the 1911 novel, his mischievous protagonist memorably saves Tiger Lily in the mermaid’s lagoon, and escapes from the ensuing scrap with Captain Hook thanks to the appearance of the ticking crocodile. What initially seems like a lucky escape, however, soon takes on a more sinister note. The water in the lagoon in rising and Peter, injured in battle, could neither swim nor fly. The rock he had clambered on top of would soon be submerged, and he was alone;

“Peter was not quite like other boys; but he was afraid at last. A tremor ran through him, like a shudder passing over the sea; but on the sea one shudder follows another till there are hundreds of them, and Peter just felt the one. Next moment he was standing erect on the rock again, with that smile on his face and a drum beating within him. It was saying, “To die will be an awfully big adventure.”

An F. D. Beford Illustration From The First Edition Of Peter And Wendy (1911)

Later in the novel, in another enduring set-piece, Wendy and the Lost Boys are captured by Hook and the pirates and kept as prisoners in the hold of the Jolly Roger. At night, they are hauled to the deck in their chains and given the ultimatum that six of them will walk the plank, and two will be spared to serve Hook as cabin boys. Having singled out Michael and John to join his crew, John asks if, as pirates they shall “still be respectful subjects of the King?”

Hook’s reply that, to the contrary, they would have to swear “Down with the King” sends the boys into rebellion and refusal, with cries of “Rule Britannia!” from the Darlings and the Lost Boys. This, alas, seals their fate, and Wendy is brought forward to send them a final message before walking the plank:

“At this moment Wendy was grand. “These are my last words, dear boys,” she said firmly. “I feel that I have a message to you from your real mothers, and it is this: ‘We hope our sons will die like English gentlemen.’”

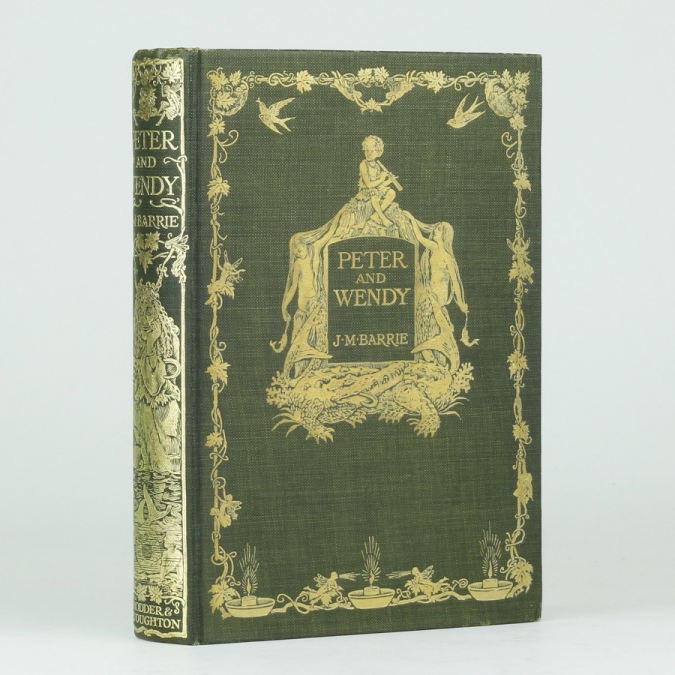

The First Edition Of Peter And Wendy (1911)

*

J. M. Barrie was introduced to Robert Scott in 1905, at a time when the former’s success with his play Peter Pan had him on course to becoming the most successful playwright of his generation, while the latter’s recent return from the Antarctic had raised his stature from that of an undistinguished naval officer to national hero and celebrity.

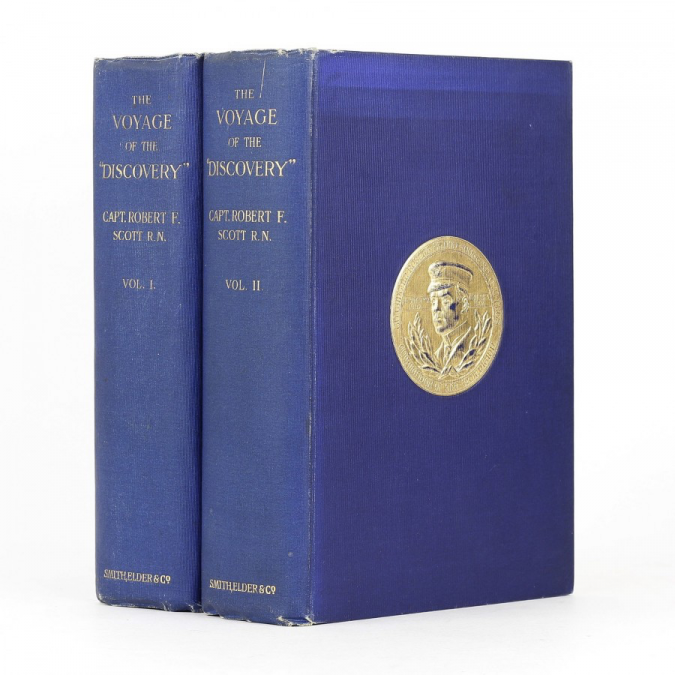

The 1901-04 Discovery Expedition was the first official British expedition to the Antarctic for nearly sixty years. In November 1902 a three man sledging party comprised of Scott, Ernest Shackleton and Edward Wilson set off towards the South Pole, making it to 82°17’ South before being forced to turn back. Scott’s account of the expedition, published in two volumes in 1905, heralded a golden age of exploration and set in the British public’s minds the seductive goal of attaining the South Pole.

Equally ready to sate the public appetite for stories of adventure was children’s literature. Ever-popular titles at the turn of the century were Charles Kingsley’s Westward Ho!, Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883), Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, and Kipling’s Jungle Books (1893-4) and it is an interesting aside that all four of these books appear in the library catalogue for books taken on the Discovery expedition.

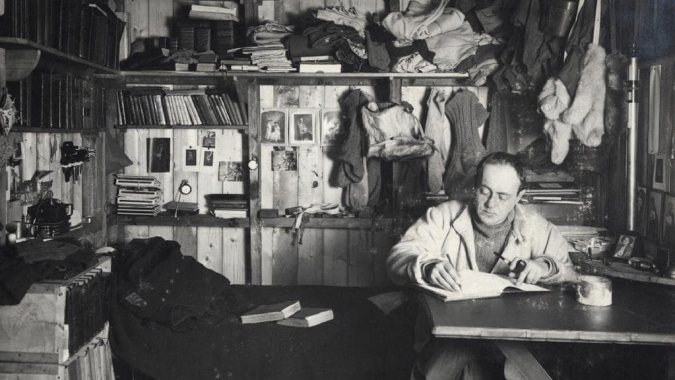

Scott In His Study At Winter Quarters, 1911 - His Makeshift Antarctic Library In The Background

The appeal of each man, near the height of Edwardian celebrity, to the other was instantly conceived. Barrie would later recall in an introduction to a volume of Scott’s journals that:

“On the night when my friendship with Scott began he was but lately home from his first adventure into the Antarctic, and I well remember how, having found the entrancing man, I was unable to leave him. In vain he escorted me through the streets of London to my home, for when he had said good-night I then escorted him to his, and so it went on I know not for how long through the small hours. Our talk was largely a comparison of the life of action (which he pooh-poohed) with the loathly life of those who sit at home (which I scorned)”

The First Edition Of Scott's The Voyage Of The Discovery (1905)

Scott would present Barrie with a copy of The Voyage Of The Discovery, which Barrie recorded that he “fell on and raced through”, and the playwright in turn treated Scott to seeing a rehearsal of Peter Pan, and the pair maintained a correspondence and intimate friendship in the coming years.

Scott married the sculptor Kathleen Bruce in 1908 and announced his second and final Antarctic expedition on 13th September 1909. Barrie had received the news from Scotland the previous week in a letter from Scott, which included an invitation to join Scott on a Naval manoeuvre, to which Barrie replied most excitedly:

“Your invitation is really the only one I have had for years that I should much like to accept. I can’t, I mustn’t, I have been doing practically nothing for so long. But I know it means missing the thing I need most - to get a new life for a bit… Altho’, mind you, I would still rather let everything else go hang and enrol for the Antarctic. Everybody should do something once. I want to know what it is really like to be alive… I chuckle with joy to hear all the old hankerings are coming back to you. I feel you have got to go again.”

The day following the official announcement, Kathleen gave birth to their only son, named Peter after the most famous character in children’s literature that decade, with Barrie chosen by Scott as godfather.

*

Much has been made of their friendship, and more of their shared values. One cannot know whether their closeness was due to an inherent shared belief in a specifically English kind of heroism and courage, or whether this was cultivated by one in the other during those inter-expeditionary years. What is undeniable is that, on the eve of Scott’s final expedition, their share belief in the nobility and heroism of exploration for its own sake shone through.

Scott had felt like he had been fighting on two fronts in the weeks leading up to his departure. On one side, he was faced against the general public who, fed by a sensationalist press, believed that the success of an expedition was measured only in proximity to 90° South. On the other, he was faced against a portion of the academic community who saw all endeavour beyond the collection of scientific data as folly.

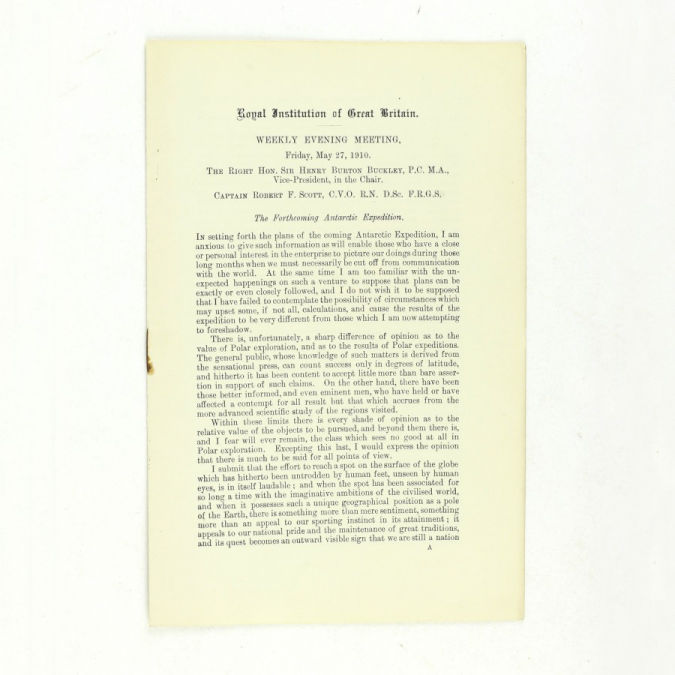

It was both of these groups that Scott addressed when he gave his final public lecture at the Royal Institution on 27th May 1910:

“I submit that the effort to reach a spot on the surface of the globe which has hitherto been untrodden by human feet, unseen by human eyes, is in itself laudable; and when the spot has been associated for so long a time with the imaginative ambitions of the civilised world, and when it possesses such a unique geographical position as a pole of the Earth, there is something more than mere sentiment, something more than an appeal to our sporting instinct in its attainment; it appeals to our national pride and the maintenance of great traditions, and its quest becomes an outward visible sign that we are still a nation able and willing to undertake difficult enterprises, still capable of standing in the van of the army of progress.

The Exceedingly Rare First Printing Of Scott's Defence Of Polar Exploration

“But though this attainment of a pole of the Earth be in itself a high enterprise worthy of national attention, it must be obvious that there are various ways in which such a project can be undertaken. It is possible to conceive the record of a journey to the pole which would contain only an account of the number of paces taken by the party, the food eaten, or the clothes worn. The interest of such a record would be entirely marred by our disappointment that so rare an opportunity to add to human knowledge should have been missed.It becomes, therefore, a plain duty for the explorer to bring back something more than a bare account of his movements; he must bring us every possible observation of the conditions under which his journey has been made. He must take every advantage of his unique position and opportunities to study natural phenomena, and to add to the edifice of knowledge those stones which can be quarried only in the regions he visits.”

*

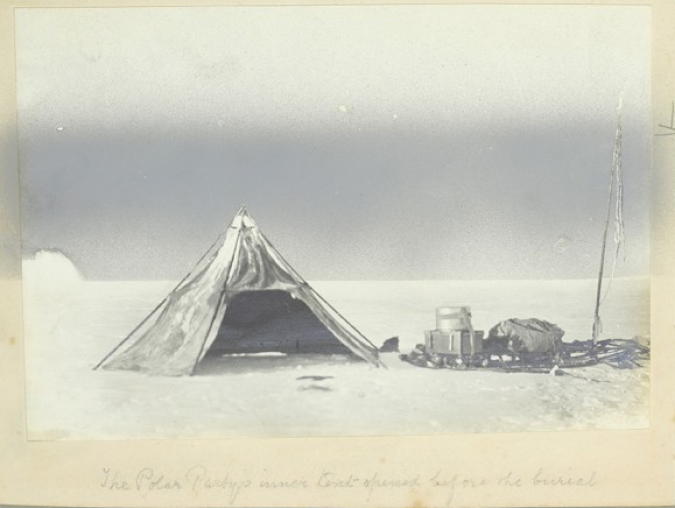

The tale of Scott and his men’s fate does not require rehashing here, but to comment on a couple of records made by Scott in his journal which seems to best reflect his and Barrie’s belief in not just heroic success, but also heroic failure.

Scott is most explicitly in Barrie’s inheritance where he describes the death of Captain Oates, almost quoting Wendy on the Jolly Roger: “We knew that poor Oates was walking to his death, but though we tried to dissuade him, we knew it was the act of a brave man and an English gentleman. We all hope to meet the end with a similar spirit, and assuredly the end is not far”

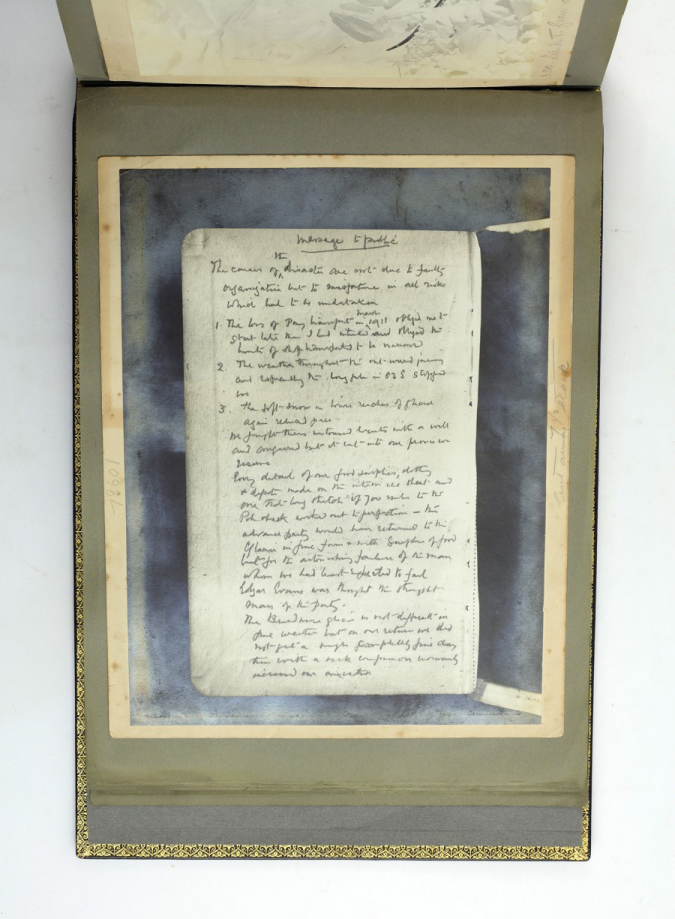

An Early Photograph Of Scott's 'Message To The People' From The Newnes Archive

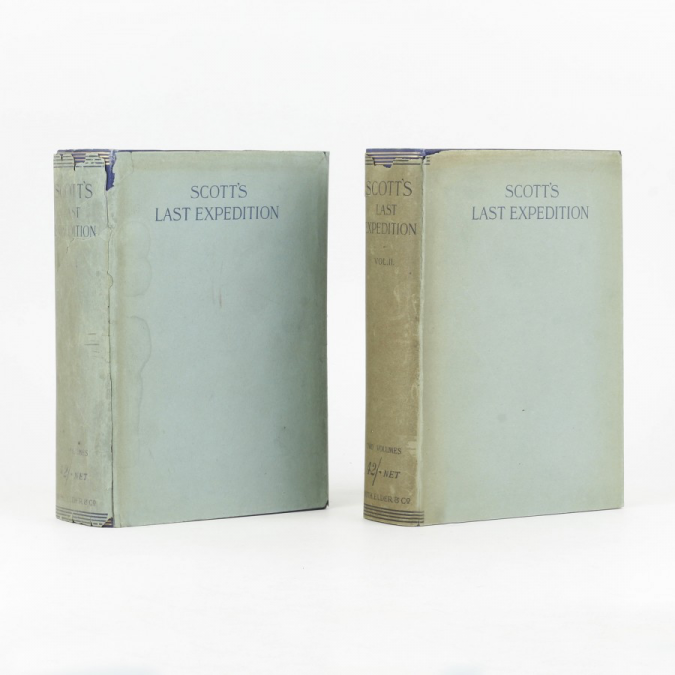

As that end drew nearer, Scott set about writing his farewell letters to those closest to him, as well as his enduring “Message To The Public”, which were later published in Scott's Last Expedition. And so, he wrote to Barrie, which rewards quoting at length:

“My Dear Barrie,

We are pegging out in a very comfortless spot. Hoping this letter may be found and sent to you, I write a word of farewell… More practically I want you to help my widow and my boy-your godson. We are showing that Englishmen can still die with a bold spirit, fighting it out to the end. It will be known that we have accomplished our object in reaching the Pole, and that we have done everything possible, even to sacrificing ourselves in order to save sick companions. I think this makes an example for Englishmen of the future, and that he country ought to help those who are left behind to mourn us… Do what you can to get their claims recognised. I am not at all afraid of the end, but sad to miss many a humble pleasure which I had planned for the future on our long marches. I may not have proved a great explorer, but we have done the greatest march ever made and come very near to a great success…

“We are in a desperate state, feet frozen, &c. No fuel and a long way from food, but it would do your heart good to be in our tent, to hear our songs and the cheery conversation as to what we will do when we get to Hut Point…

“As a dying man, my dear friend, be good to my wife and child. Give the boy a chance in life if the State won’t do it. He ought to have good stuff in him. I never met a man in my life whom I admired and loved more than you, but I could never show you how much your friendship meant to me, for you had much to give and I nothing.”

The First Edition Of Scott's Last Expedition, Where His Journals, Including The Letter To Barrie Were First Published.

After news of Scott’s fate reached England a fund was established to support those, such as Kathleen and Peter Scott, who were dependent on those who died on the expedition. This was initially met with a poor response and so Barrie took up his pen and published an appeal:

“Things are not going too well with the various schemes started to honour the men who have done so much to honour us. Almost every Briton alive has been prouder these last days because a message from a tent has shown him how the breed lives on; but it seems almost time to remind him of that more practical Englishman who said of a friend in need, “I am sorry for him £5; how much are you sorry?” Of every 100 who are proud of those men in the tent some 99 have not yet said how proud they were.”

The effect of Barrie’s appeal was extraordinary, and having been first published in The Time on February 19th 1913, it was soon circulated around the other London papers. The public response swelled the fund to double its original target, and so Barrie had granted his friend his dying wish.

This is perhaps all the more remarkable as Barrie did not yet know of the letter Scott had written him. This he received from Kathleen Scott two months later, and the flimsy sheets extracted from Scott’s journal would live in his breast-pocket for the rest of his life.

These sheets were in his pocket when, in 1922, he gave his rectorial address at the University of St Andrews. Around halfway through his lecture, entitled “Courage” he pulled the sheets from his breast-pocket and read the undergraduates the letter Scott had written him. He implored them to imagine themselves standing “for a moment by that tent and listen, as he says, to their songs and cheery conversation.” Later he muses “What is beauty? It is these hard bitten men singing courage to you from their tent; it is the waves of their island home crooning of their deeds to you who are to follow them.”

Click Through Below For:

- J. M. Barrie & Peter Pan First Editions

- Rare Books Related To Captain Scott & The Antarctic

- A Recent Blog On Scott's Fellow Explorer Ernest Shackleton

- If you have any questions about the books featured here, click here to email Tom

Comments

Recent Posts

- The Evolution of Crime

- Tour The Bookshop On Your Screen

- The Genesis of Mr. Toad: A Short Publication History of The Wind In The Willows

- Frank Hurley's 'South'

- The "Other" Florence Harrison

- Picturing Enid Blyton

- Advent Calendar of Illustration 2020

- Depicting Jeeves and Wooster

- Evelyn Waugh Reviews Nancy Mitford

- The Envelope Booklets of T.N. Foulis

- "To Die Like English Gentlemen"

- Kay Nielsen's Fantasy World

- A Brief Look at Woodcut Illustration

- The Wealth Of Nations by Adam Smith

- What Big Stories You Have: Brothers Grimm

- Shackleton's Antarctic Career

- Inspiring Errol Le Cain's Fantasy Artwork

- Charlie & The Great Glass Elevator

- Firsts London - An Audio Tour Of Our Booth

- Jessie M. King's Poetic Art, Books & Jewellery

Blog Archive

- January 2024 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- August 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (1)

- July 2020 (2)

- March 2020 (3)

- February 2020 (2)

- October 2019 (2)

- July 2019 (2)

- May 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (2)

- February 2019 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- November 2018 (1)

- October 2018 (2)

John Constable 26/Mar/2020 13:49

Very moving when one considers the degree to which we have all become so selfish and and obsessed with nothing more than our own narrow interests.