The legendary silent film of Shackleton’s famous expedition, digitally remastered for the centenary of his death.

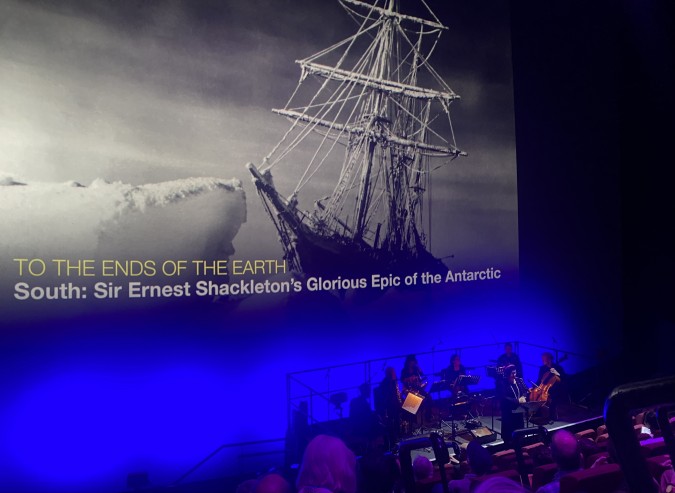

At the BFI on Thursday evening, they were unveiling a new digital remastering of Frank Hurley’s South (1919) – the legendary documentary of Shackleton’s Endurance expedition. Seeing the film on the IMAX screen, accompanied by a live orchestra, with icebergs fifty feet tall towering in front of you, was an extraordinary experience.

The decision to have Frank Hurley on the expedition as not just a photographer, but as a documentary filmmaker was revolutionary. Documentary film was at an embryonic stage, and public lectures embellished with lantern slides dominated this form of entertainment.

Frank Hurley had previously been the expedition photographer and filmmaker for Douglas Mawson’s Australasian Antarctic Expedition, and had only returned to Adelaide in February 1914. Scarcely eight months later, he boarded the Endurance in Buenos Aires and headed south with Shackleton’s men. Returning from the Antarctic was a common difficult of explorers, with Hurley writing that, “after life in the vastness of a vacant continent, civilisation seemed disappointingly narrow, cramped, superficial and empty. A couple of weeks it sufficed to bring on an attack of wander fever.”

The middle section of the film shows the attempts to free the Endurance from the pack ice. In one particularly dramatic shot, Frank Hurley has taken his camera down to the floe immediately in the ship’s path, and stood there filming the bow of the vessel as it charged towards him. As it approached him, the impact split the ice floe Hurley was stood on, and in the surviving film one can see – from Hurley’s point of view – this crash throwing him to one side.

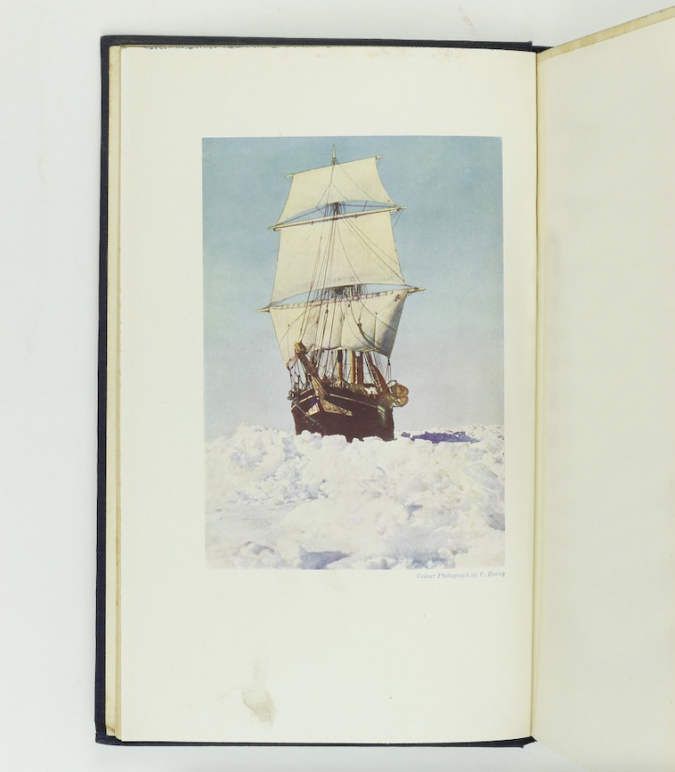

The Endurance trapped in the ice, frontispiece to Shackleton's South

The slow destruction of the Endurance by the ice it was trapped by, nearly claimed the film we see here. Having decided that their next move would be to try and reach Paulette Island, Hurley was faced with having to save his film and negatives from the crumbling wreck of the Endurance:

“I went down to the wreck with one of the sailors to make a determined effort to rescue my films and negatives. We hacked our way through the splintered timbers and after vainly fishing in the ice-laden waters with boathooks, I made up my mind to dive in after then. It was might cold work groping about in the mushy ice in the semi-darkness of the ship’s bowels, but I was rewarded in the end and passed out the three precious tins.”

They needed saving too. A significant sum of money had been advanced against the film rights to help finance the expedition, so it was important that if they were to return home, they had the record of their journey. At this stage the whole party had to carry on only carrying the bare essentials. So Shackleton and Hurley went through the 520 glass plate negatives, destroying 400 of them and keeping just 120. All of Hurley’s further photographic equipment was abandoned, and he took on with him only one small camera, and three spools of unexposed film.

A still from Frank Hurley's South (1919)

When they reached Elephant Island, the cans of film were buried in the permafrost which, as roughly -5 degrees Celsius, is the same temperature as the BFI’s archival store – ideal for preserving the film. With his film buried, and not accompanying the small party Shackleton took on the remarkable voyage of the James Caird, the remainder of South is taken from footage shot by Hurley when he returned to South Georgia in 1916.

The film was used in lectures and talks given by both Shackleton and Hurley after their return home. Then in 1926, the film rights were bought by Sir William Jury, who issued it as a standalone film in 1933, with commentary by Frank Worsley. Since 1955 the reels have been in the safe keeping of the BFI, and are once again kept below freezing in their master film store.

The film in the BFI's master film store

The survival of the film, just as the survival of all of Shackleton's men, is against the odds, As the BFI's Bryony Dixon has written:

"With all the bad things that can happen to film stock and the mechanics of cameras in the extremely low temperatures of Antarctica – where the oil freezes jamming the mechanisms and can tear the fragile film – the celluloid seems to have returned in astonishingly good order. Of course, Hurley only had half a film as the camera was left behind, missing all that drama, and is still presumably home to brittle stars at the bottom of the South Atlantic."

Hurley later wrote that:

“I have tried to tell of the wonders we saw; of the dangers we faced; of the glamour of being the first to penetrate the unknown; of our successes, and of our failures – just as glorious – and to pictures the incredible beauties, as well as the awesome desolation, of that vast unpeopled continent – Antarctica.”

And yet, as glorious as the bright icy white of the scenery looks on screen, and as dramatic as the scenes of the Endurance breaking through ice floes are, some of Hurley’s most moving images are the intimate character studies of some of the crew, which can be seen in the clip below.

The digitally remastered film is in cinemas from today, Friday 28th January. I would highly recommend it for anyone with an interest in polar history, or if you have ever been captivated by this remarkable story of survival.

To view our current stock of material related to Polar Exploration click here.

Comments

Recent Posts

- The Evolution of Crime

- Tour The Bookshop On Your Screen

- The Genesis of Mr. Toad: A Short Publication History of The Wind In The Willows

- Frank Hurley's 'South'

- The "Other" Florence Harrison

- Picturing Enid Blyton

- Advent Calendar of Illustration 2020

- Depicting Jeeves and Wooster

- Evelyn Waugh Reviews Nancy Mitford

- The Envelope Booklets of T.N. Foulis

- "To Die Like English Gentlemen"

- Kay Nielsen's Fantasy World

- A Brief Look at Woodcut Illustration

- The Wealth Of Nations by Adam Smith

- What Big Stories You Have: Brothers Grimm

- Shackleton's Antarctic Career

- Inspiring Errol Le Cain's Fantasy Artwork

- Charlie & The Great Glass Elevator

- Firsts London - An Audio Tour Of Our Booth

- Jessie M. King's Poetic Art, Books & Jewellery

Blog Archive

- January 2024 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- August 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (1)

- July 2020 (2)

- March 2020 (3)

- February 2020 (2)

- October 2019 (2)

- July 2019 (2)

- May 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (2)

- February 2019 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- November 2018 (1)

- October 2018 (2)

Topher 23/Mar/2022 03:42

big fan!!!