A. A. Milne, a fervent champion of The Wind In The Willows, wrote in the introduction to the first illustrated Arthur Rackham edition (1940): “The book is a test of character. We can’t criticise it, but it is criticising us… You may be worthy [of the book]: I don’t know. But it is you who are on trial.”

The story was born on the banks of the River Thames, in the mind of a small boy who grew up in the Berkshire village of Cookham Dean. Kenneth Grahame was born in 1859 and, as a result of various tumultuous events in his personal life, was raised by family guardians in a delightful country house just a stone’s throw from the river. He spent much of his childhood “messing about in boats”, just as his infamous animal characters would later come to do.

Though an outstanding pupil, Grahame was denied the opportunity to attend Oxford University due to the limited financial means of his guardians, and so began work at the Bank of England in 1879. But, as a true lover of the great outdoors, he spent much of his time daydreaming of the English country and cosy firesides. Such scenes would grace the pages of his literary masterpiece in later years.

Some two years after beginning work in the city, Grahame married Elspeth, before their family became three only a year later with the arrival of Alastair, affectionately known as “Mouse”. In May 1904, just around bedtime, Mouse was reluctant to settle down to sleep, and so assigned his father some categories for stories. Among these were moles, giraffes, and water-rats, and the storytelling went on till after midnight. Within these tales, a character named Toad, "a good fellow, a very good fellow, but vain", sprang from Grahame’s imagination, developing in the months to come in further bedtime stories and letters to Mouse. And so began the making of one of the world's most loved children's stories, The Wind in the Willows, right there in the bedroom of a small “Mouse”.

Grahame was keen to publish the book with his former US publishers of The Golden Age (1895) and Dream Days (1898), but they weren’t much impressed with the story due to its change in tone and use of animal characters, not to mention the negative feedback from literary critics of the day. As Milne later stated: “The first two books had been about children such as only the grown up could understand; this one was about animals such as could be loved equally by young and old. It was natural that those critics who had saluted the earlier books as masterpieces should be upset by the authors temerity in writing a different sort of book.”

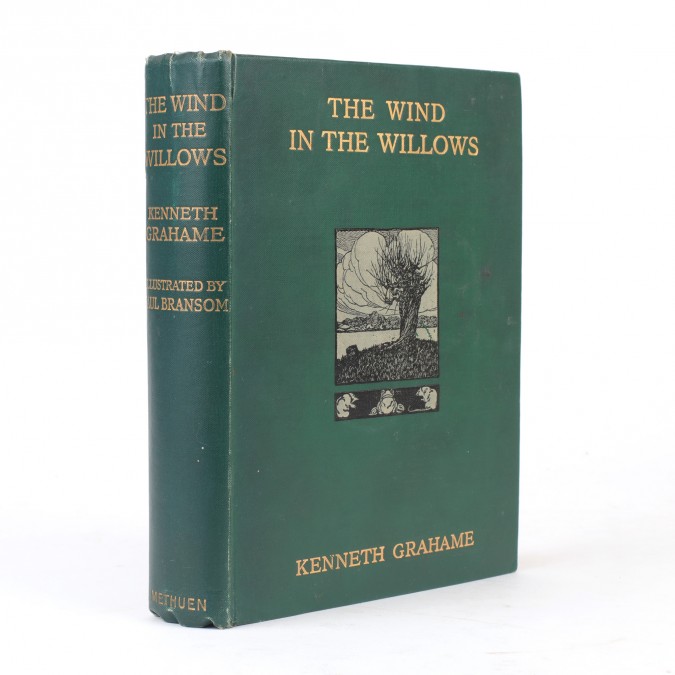

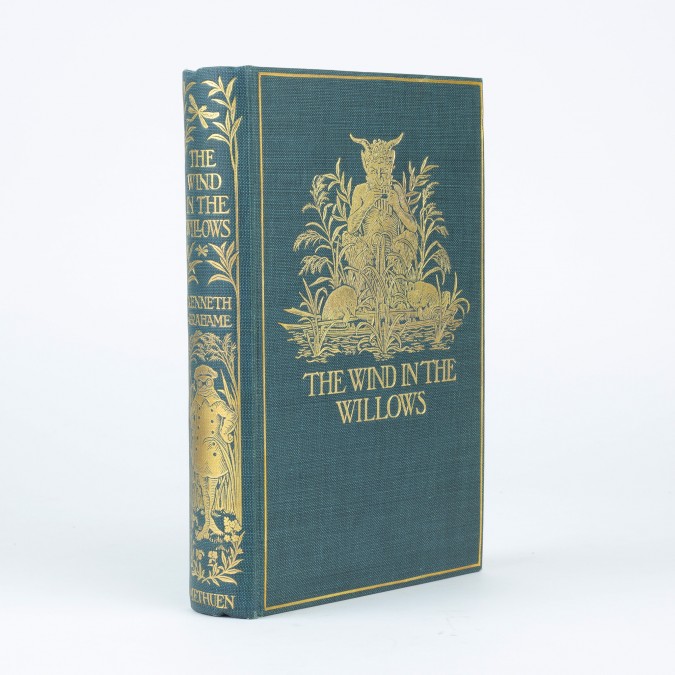

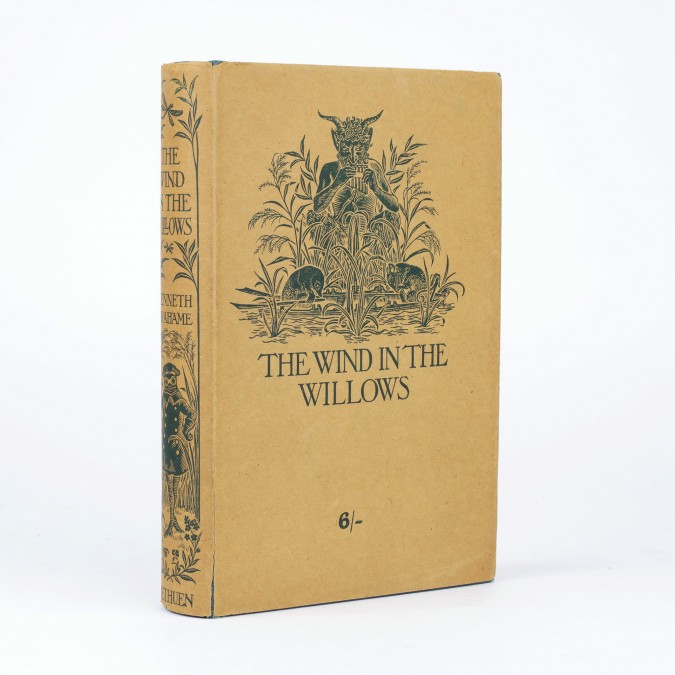

The first edition of The Wind In The Willows came into the world in October of 1908, published by Methuen in London and Scribners in New York. It was a beautifully produced book, blocked in gilt and issued with a printed dustwrapper priced at six shillings.

The book was an immediate success with the reading public. The greatest appeal of the novel is now (and then) considered to be its sense of setting. Grahame once told his wife that what moved him most were places, and the community of wildlife which occupied them: “I like most of my friends among the animals more than I like most of my friends among mankind”.

Praise too came from overseas, with President Theodore Roosevelt writing to Grahame in January 1909, saying “I have read it and reread it, and have come to accept the characters as old friends; and I am almost more fond of it than of your previous books.”

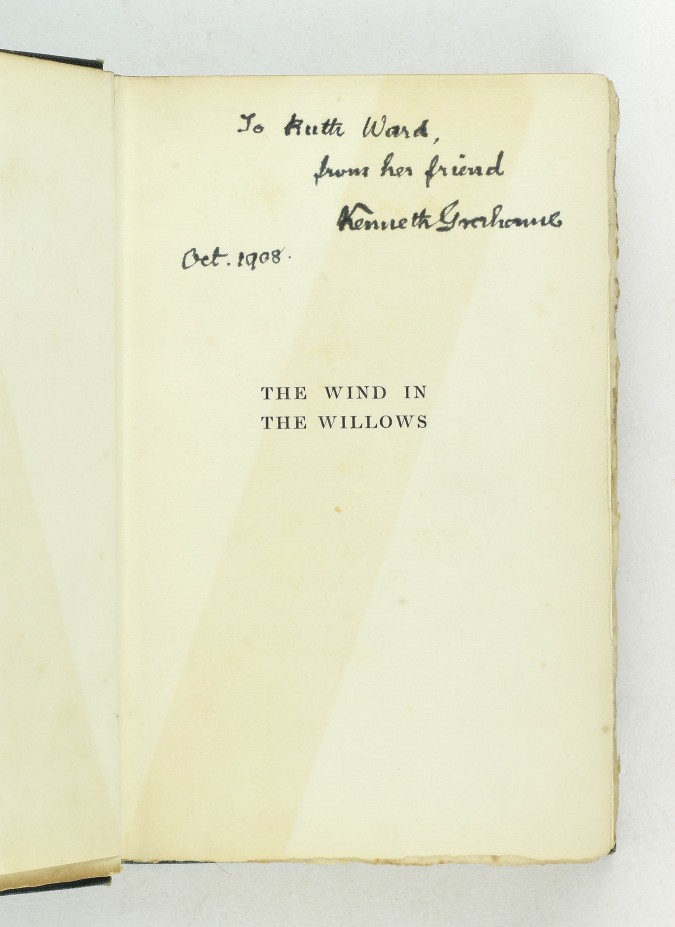

Picking up one of the first editions assigned to him by his publishers, Grahame inscribed it on the front free endpaper to Ruth Ward, the daughter of his colleague and friend, Sydney.

Sydney’s wife Katherine had been the first to hear of the origin of The Wind In The Willows at bedtime in a letter dated May 1904, and all of the Wards had been greatly interested in the development of the story. In a letter to Ruth, Grahame’s wife Elspeth writes, “I thought you might like perhaps better than anything else a new book that Mouse’s Daddy has just written, so I asked him for one for your birthday present. I want to know how you like it.” This copy is one of only six extant author's copies of the first edition, inscribed by Grahame on publication.

The success of the first edition was such that a second edition was published in the same month in an identical format. This time, Grahame thought of his friend Austin M. Purves, a Philadelphia-based businessman whom the Grahame’s met while on holiday at their beloved Fowey in 1907. Purves, being an important figure in artistic circles, sought to help his author friend by writing a most favourable review of the American edition of The Wind In The Willows in a US magazine. In reply, Grahame wrote in a letter: “I’m most awfully obliged to you for the solid work you are putting in on behalf of ‘the W. in the W.’ Your review was perfectly charming, & is bound to be most helpful. That the book has given you all personal pleasure is of course very good for me to think of.” Turning to the front free endpaper of one of the freshly printed second editions, Grahame penned a rare dedication to his friend: “Austin M. Purves / with greeting, + all the good wishes of the season, from Kenneth Grahame, Christmas 1908”.

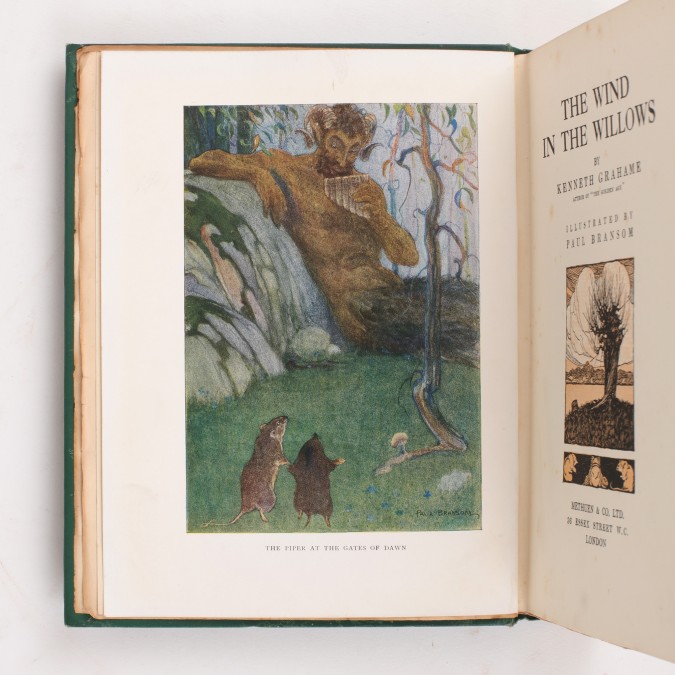

Several illustrated versions of the book were published in the years to come, with the first fully illustrated edition appearing in 1913 with illustrations by Paul Bransom. This edition included Graham Robertson's original frontispiece, featuring cherubs by a stream, and ten of Bransom's vibrant colour illustrations.

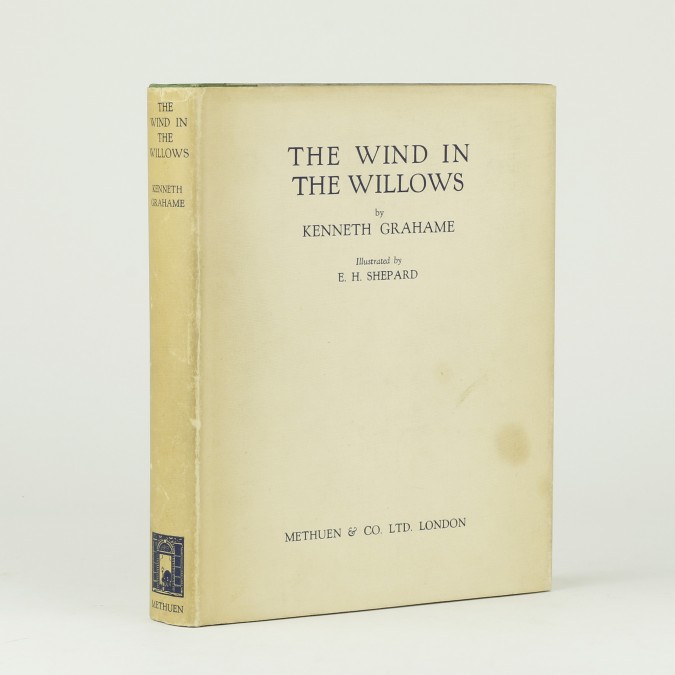

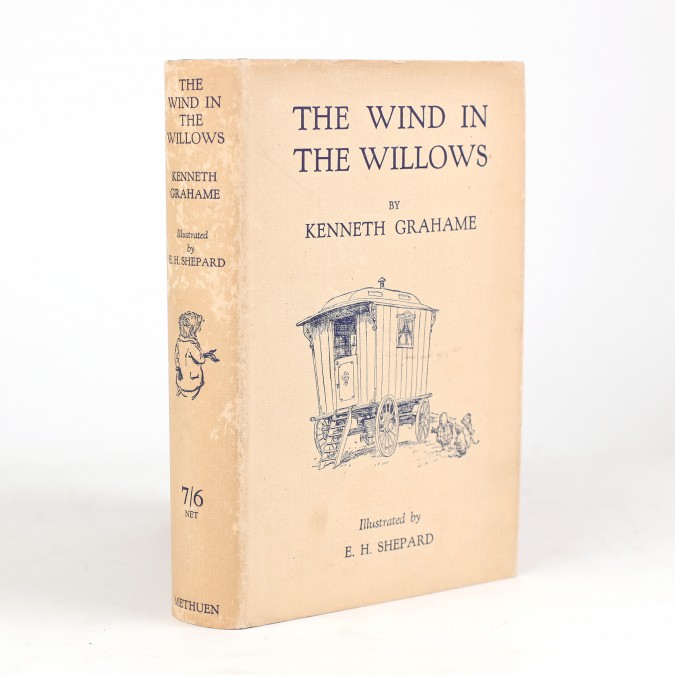

Bransom may have been the first illustrator of The Wind In The Willows, but many other significant editions were to come. Fresh from the success of his collaboration with A. A. Milne on the Winnie the Pooh books (and very likely drawn in by Milne's recommendations), E. H. Shepard came to illustrate the now most famous and popular illustrations of The Wind In The Willows in 1931. "I love these little people; be kind to them,” was the instruction given by Grahame to Shepard when the illustrator agreed to create drawings for the book. At a meeting with Grahame, now armchair ridden due to illness, Shepard recalled the author regretting not being able to personally show him the places along the Thames which inspired the book, and that he would have to find his way alone.

Shepard’s illustrations were published in a deluxe limited edition of only 200 copies. A trade edition was also released simultaneously, featuring maps of the homes of Grahame's beloved characters for endpapers.

A very small number of the first trade editions signed by both Grahame and Shepard are also known. Shepard excelled at breathing life into Grahame's narrative and characters, and his illustrations have barely been out of print since. The fame of Grahame’s characters owes a great deal to Shepard’s timeless work.

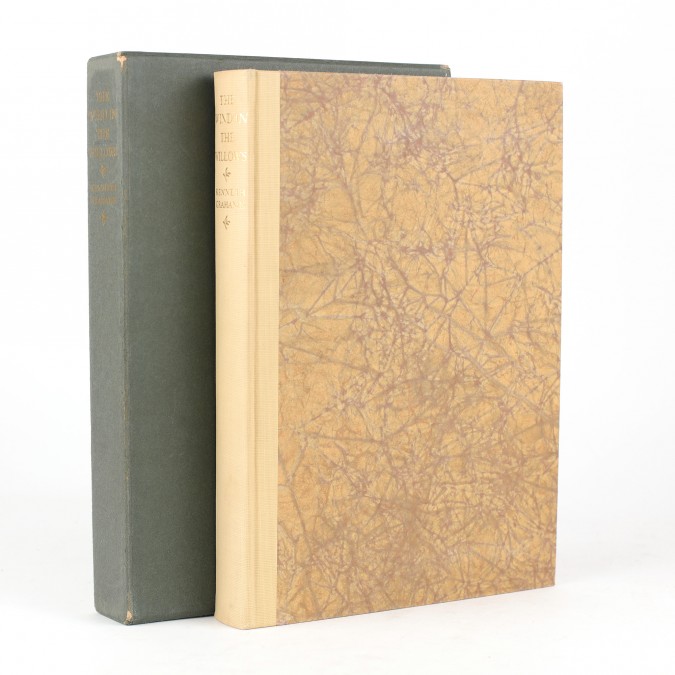

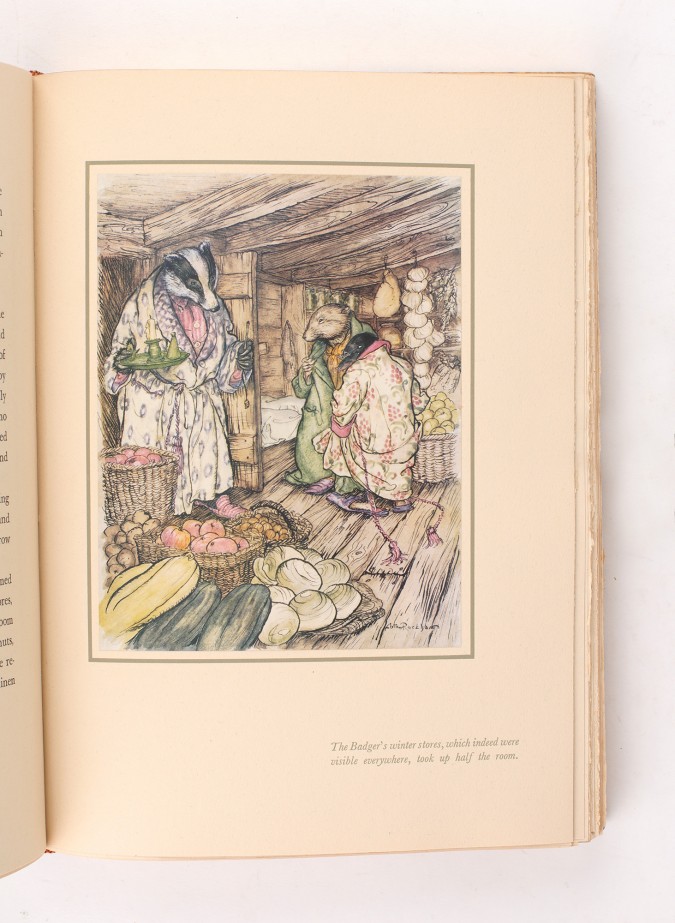

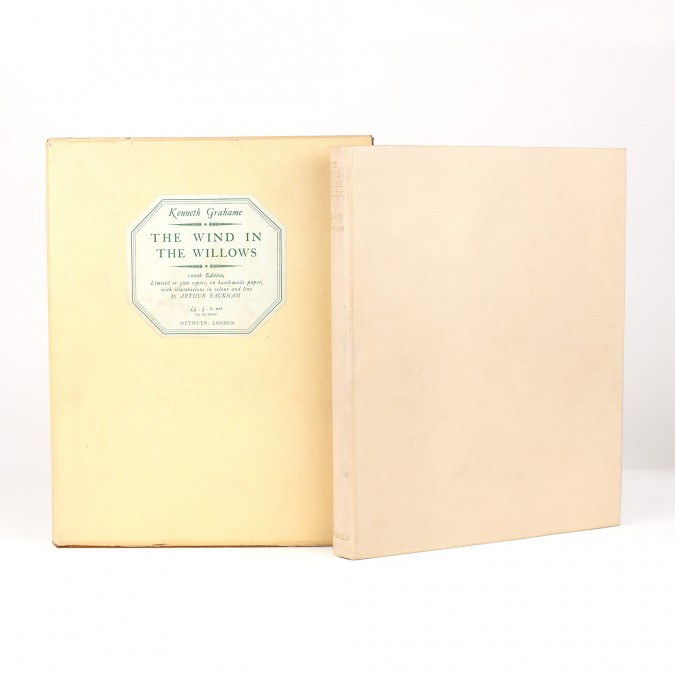

Grahame initially wanted Arthur Rackham, best known for illustrating Rip Van Winkle and Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, to illustrate The Wind In The Willows. However, Rackham initially declined the author’s offer around the time of publication as he was too busy working on A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1908). Around thirty years later, however, Elspeth invited Rackham for a walk along the Thames to view the many places and sights which inspired the stories lovingly created by her now deceased husband (d. 1932). He finally accepted and, amid the outbreak of WWII and personal illness, prepared a series of sixteen illustrations and several line drawings for the tale. This was his last project. Upon completion, the dying artist is said to have sunk into his pillow and said: “Thank goodness, that is the last one”. His drawings were published posthumously in by the Limited Editions Club in New York in 1940.

After the war, a British edition with Rackham's illustrations was published by Methuen to commemorate the 100th edition of The Wind In The Willows in 1951. The choice was made to have the book bound in a now notoriously fragile full white calf, and to limit the edition to only 500 copies. As further testament to the lasting influence of the book, A. A. Milne, writer of the play Toad of Toad Hall, influenced, of course, by Grahame’s tale, wrote and introduction the edition.

In this, he spoke fondly of the book which meant so much to so many, and the ongoing influence of the characters Mr. Toad, Ratty, Badger, and Mole for readers young and old. Indeed, in the eighty years since Milne’s introduction, over ninety illustrators, countless editions, museum galleries, exhibitions, films and plays have recreated the imaginary community of “little people” on the Thames, first conjured up at bedtime. Yet it is undoubtedly these important editions in the story’s early years which hold the greatest secrets and stories behind the many people (and Toads) which created it.

Comments

Recent Posts

- The Evolution of Crime

- Tour The Bookshop On Your Screen

- The Genesis of Mr. Toad: A Short Publication History of The Wind In The Willows

- Frank Hurley's 'South'

- The "Other" Florence Harrison

- Picturing Enid Blyton

- Advent Calendar of Illustration 2020

- Depicting Jeeves and Wooster

- Evelyn Waugh Reviews Nancy Mitford

- The Envelope Booklets of T.N. Foulis

- "To Die Like English Gentlemen"

- Kay Nielsen's Fantasy World

- A Brief Look at Woodcut Illustration

- The Wealth Of Nations by Adam Smith

- What Big Stories You Have: Brothers Grimm

- Shackleton's Antarctic Career

- Inspiring Errol Le Cain's Fantasy Artwork

- Charlie & The Great Glass Elevator

- Firsts London - An Audio Tour Of Our Booth

- Jessie M. King's Poetic Art, Books & Jewellery

Blog Archive

- January 2024 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- August 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (1)

- July 2020 (2)

- March 2020 (3)

- February 2020 (2)

- October 2019 (2)

- July 2019 (2)

- May 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (2)

- February 2019 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- November 2018 (1)

- October 2018 (2)

Graham Rylatt 15/Jan/2024 14:41

I am 72 years old and have just began reading the Wind in the Willows for the fith time during my life.

I have loved the book all my life, it is a Children's book for Adults and, in my opinion, one of the great pieces of English Literature.

If you read this book and do not enjoy every wonderfull page, thier is something in life that you have missed