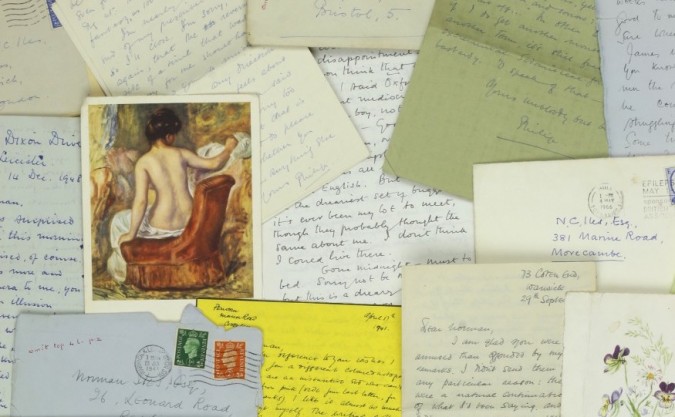

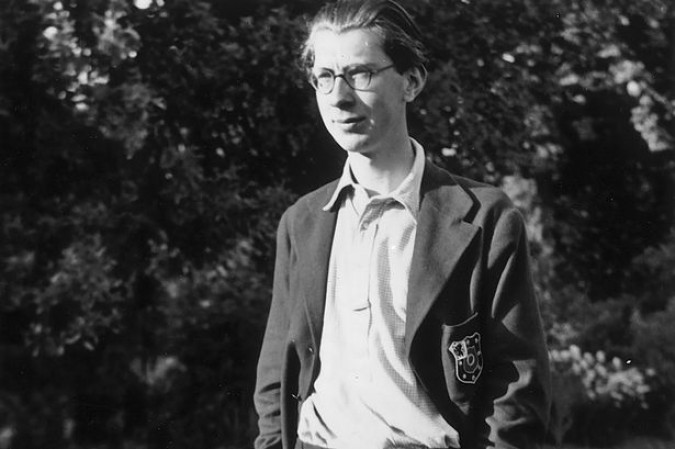

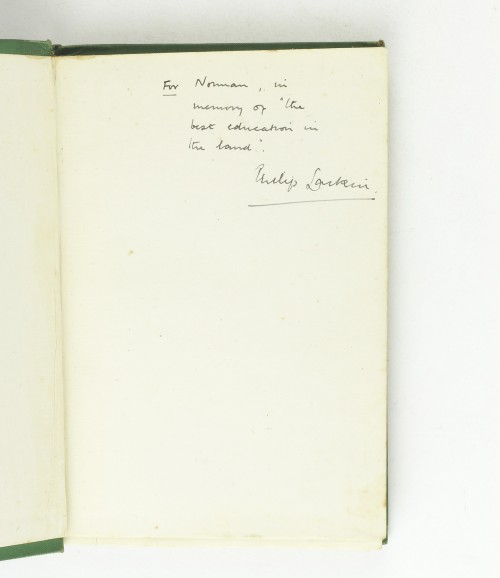

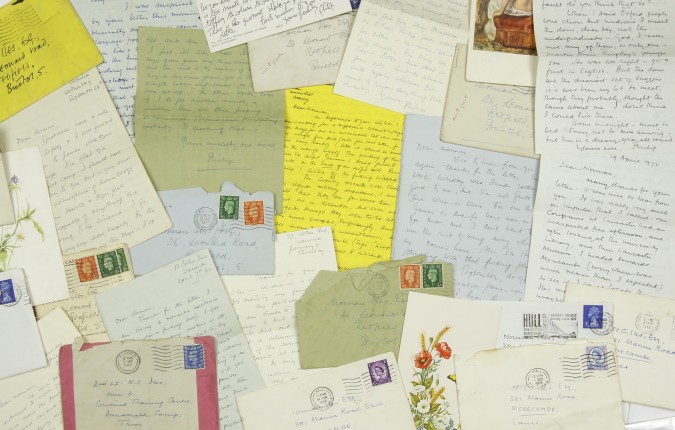

We have just had the pleasure of studying and cataloguing this archive of letters written by Philip Larkin to Norman Iles, one of his closest friends at Oxford. The archive comprises a forty-one year correspondence, spanning virtually Larkin's entire adult life, and begins during their first Easter vac after going up to Oxford (April 1941), with Larkin stoically reporting on the aerial bombardment of his hometown Coventry, "Balls to airraids. The sun still shines" (17th April 1941). Iles was Larkin's tutorial-mate at St John's College, and quickly became a close friend; the first outside of the small group of Oxford acquaintances whom he had known from school.

It proceeds to take in discussions on literature, friendship, love, sex, jazz and education. The war, too, was never far from Larkin's mind in his writing. The thirty-one letters from Larkin throughout the 1940s are all expansive in subject matter and thought, and have the often inventively expletive-ridden contempt for authority and pretence that defined their circle later to be refined by Larkin as a principal characteristic of Movement poets. Those written during the war, in which Larkin did not serve but Iles did, are long (with just one exception they are between four and ten sides of paper each).

The literary influences, indulgences and hatreds of Larkin the undergraduate and fledgling poet-novelist are presented with candour in these early letters, whether enthusing about D. H. Lawrence (a mutual hero) or dismissing a compulsory text from his course, "when I don't read Middle Eng. I'm supposed to read Wordsworth, & vice versa. There's nothing in Wordsworth that D.H.L. hasn't done 20 times better" (30th December 1942). He expands on this point in a later letter, "There's so much to be learnt - and of course the best thing to have is a 'genuine love of literature'. I haven't got one, and I don't know a shop where they sell them. In consequence, I shall find it difficult to convince the examiner that I feel strongly about Pope, or Shelley, or 'The Wanderer' or Whatever it is" (17th April 1943). In spite of his general rejection of set texts, Larkin was convincing enough to get a first, and wrote excitedly to Iles to tell him. "This is so dumbfounding... I always worked on the principle that if you throw enough mud some will stick... and the resultant farrago of irrelevant information, misapprehensions, sloppy sentiment, conventional viewpoints, third-hand ideas, & murderous similes ("Milton's sonnets are leaves floating down the great river of his main work" etc) was, in my opinion, so worthless that I honestly thought I could never do better than a second" (19th July 1943).

The social milieu that Larkin and Iles curated at Oxford, notably the group that came to be known as 'The Seven', is analysed in great detail: "you must understand that my friends reflect my virtues and vices... you encompass a very large part of my vices" (24th September 1941). This thought Larkin develops at length in his next letter, a seven side dissertation on friendship: "What I was really trying to say was that if I appear sulky and quarrelsome, you mustn't be mortally offended... Friend can mean three things - acquaintance, comrade, or antagonist. Brown is my acquaintance, James is my comrade, you are my antagonist... We've all a long way to go yet, and it's silly to think we are finished and finite characters, with finished and finite relationships. You must take what you want from me; and I shall from you... We are both (you and I) intellectuals. We depend on language and tend unconsciously to judge people by our standards" (29th September 1941).

Their correspondence on the subject next picks up during the Christmas vacation, yuletide in Warwick not having been greatly enjoyed by Larkin: "miserable, nostalgic, bored, depressed, frightened, irritable and generally shat about" (28th December 1941). The relationship analysed most by Larkin over the series of letters that follows is that between himself and Philip Brown, a medical student who formed part of The Seven. Most accounts of Larkin's Oxford years mention Brown as a brief homosexual interest that Larkin quickly grew out of and most descriptions are based on hearsay and the euphemistic North Ship poem 'I Dreamed Of An Out-Thrust Arm Of Land'. Indeed, Andrew Motion concludes in the latest edition of his biography of Larkin "[he] made no mention of his feelings for Brown in letters to other friends" (Philip Larkin: A Writer's Life Faber, 2018). How ever, in these Christmas letters to Iles, and in two further letters in April and July 1942, Larkin is explicit in his feelings, discusses the holiday to Gower with him that inspired the aforementioned poem and admits, "my whole attitude is coloured violently by wanting to be alone with Philip" (8th January 1942). Of the five long letters Larkin wrote Iles in this sequence, only two were published in Anthony Thwaite's Selected Letters Of Philip Larkin (Faber, 1992) and even then were heavily redacted to omit those sections that discussed Larkin and Brown.

The war letters also provide excellent demonstrations of Larkin's wit and contempt for authority. "I see we have finally finished Rommel in Africa. Philip and I stood to attention when the midnight bulletin was read out and sang 'God Rape The King'. (I hope some fucking censor reads this.) Which reminds me I heard from James - a letter posted on the boat. The censor hadn't found anything to censor for security reasons so he'd crossed out all the swear-words, e.g. 'The sea looks warm and contented, as if it had just had a good ////'" (8th November 1942). That same letter served also as a delivery mechanism for an original piece of homosexual doggerel.

On 10 November 1943 Larkin wrote to Iles in typically lugubrious terms about the opening of his post-Oxford life: "The job which prevents me from coming to Oxford is that of librarian at Wellington. It's not where the school is, nor in New Zealand, in fact I am not sure where it is except that it is not far from Wolverhampton. Anyway it has no librarian & this little nest I am trying to crash with the aid of my First and a servile manner which will make them think correctly that they can bully me."

After Oxford, Larkin set about trying to get published and naturally the letters served both fledgling writers as a means of giving each other feedback in their writing and updating each other on their endeavours. "I have finished a wittily pornographic story about a girls' school," Larkin wrote to Iles, "and am embarked upon a serious one now about a scholarship boy at Oxford. Silly little brute..." (19th July 1943). The former is the school story Larkin wrote that year under the pseudonym Brunette Coleman - Trouble At Willow Gables. The latter is the beginnings of his first novel, Jill. By 1944, Larkin declares himself absolutely committed to the artist's life, "You see, my trouble is that I simply can't understand anybody doing anything but write, paint, compose music I can understand their doing things as a means to these ends, but I can't see what a man is up to who is satisfied to follow a profession in the normal way" (16 April 1944).

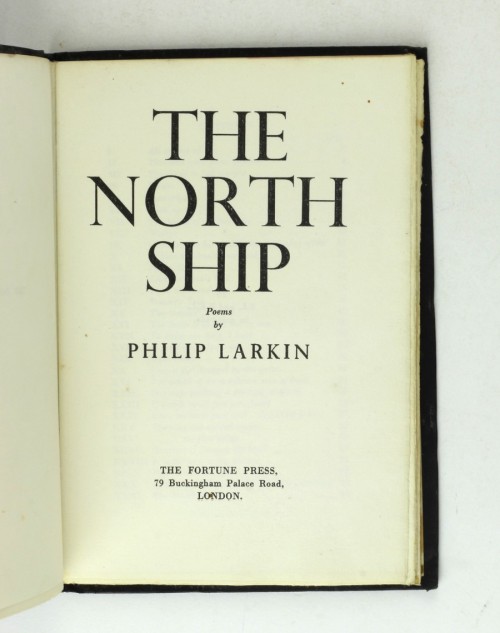

The letters from this period also provide an outlet for Larkin's frustrations in trying to get his novel into print. His chosen outlet, the all-but vanity publisher The Fortune Press, is the main focus of his ire, "The only way of publishing I know is the Fortune Press They don't pay anything, but nobody will unless you're established It will be funny to be paid for a book, if I ever am - sort of unreal. But then, I probably never shall be" (25th February 1945). When he updated Iles eight month later, his temper had rather run out; "I had hoped to send Jill when I next wrote, but the sons of sods are still delaying and delaying, till my heart boils with anger and great knotted veins stand out on my forehead." (25th October 1946). Larkin uses the same letter to give Iles advice on tightening up his poetry, something he did throughout this period: "I liked the simplicity of your poem and its fine last line. For form's sake I should like it put in 4 pairs of lines - run lines 1-2 together and rewrite 8-9 to form one line and avoid the cliche 'bask in the sun'".

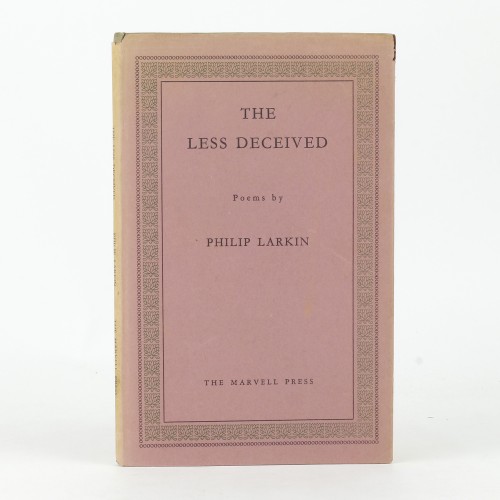

Iles continued to write prolifically, but to little acclaim, and had a large family and idealistic left-wing politics. The two men were leading different lives; a point observed well by Larkin "I just trudge through my years, every one the same, sewn up bachelor occasionally publishing a poem - whereas I imagine you as some vast-bellied burgher from a Dutch painting, surrounded by children, full of love and tolerance" (6th February 1973). Nevertheless, they continued a friendly correspondence and the archive includes twenty-seven letters and cards from 1950 onwards. The letters in the 1950s are focused, almost the the exclusion of all other subjects beyond idle catching up, on poetry. In the first three letters from this section, Larkin offers a long responses, capturing encouragement and gentle criticism of two groups of Iles's poems: "I liked reading it very much; it has a warm, generous spirit about it, a courage too, that is unique among my circle of friends" (15th January 1950). Larkin was five years from publishing his first mature collection of poetry, The Less Deceived, put was already writing the work that would be collected there. His criticism demonstrates a development of the acute keenness for the single clear image that would be the feature of his future work, "I think you are much acuter - or I understand much more what you are getting at - when dealing with preciser terms of reference" (ibid). In the second of these letters, written the year after The Less Deceived was published, Larkin is more explicit in his philosophy of poetry: "poetry doesn't live by feeling alone: the feeling is the dynamo that drives one's talent to find the rhythms and words appropriate to it (the feeling), or more than just appropriate to it - that will immortalise it" (5th November 1956). In the third he comments prematurely "I hope you are right about our continuing to sit by the fire producing poems: I very much doubt if I shall" (9th January 1958). Eight months later he would write to Iles "attempts to write poetry come to nothing, partly through lack of time and partly through through lack of inspiration. I think my poetry comes in 10-year gushes! I mean the next lot is due about 1960-63" (10th August 1958). He was eerily accurate here - The North Ship was published in 1945, The Less Deceived in '55, The Whitsun Weddings in 1964 and High Windows in 1974.

The writing, not-writing, publication and reception of these final two collections are also the focus of the later letters. "I have also just sent off a new collection of poems", Larkin wrote in June 1963, " very thin stuff At present it is called THE WHITSUN WEDDINGS." (12th June 1963). This is followed by reports, as in the periods following the publication of his previous collections, of not writing "I haven't written anything for getting on for three years. Don't suppose I shall, now, until some major unhappiness kicks me in the pants. Happiness isn't productive, for me!" (5th October 1965). In his letter of 6th February 1973, Larkin enclosed a facsimile typescript of 'The Old Fools', "to cheer you up". The poem was published in Listener five days beforehand. Larkin's response to Iles's praise of his final collection, High Windows, neatly demonstrates the discomfort he felt with his success "I'm glad you liked some of the poems: nothing one writes can ever equal the complications of life, though I rather like 'Annus Mirabilis' - English Social History, by P. A. Larkin. It's not specially meant to be funny. I really do think something like that happened." (22nd July 1974).

Larkin also comments on his personal life and on life as a librarian, "there is a faint fascination in being so very much at the end of the line, and in knowing that beyond you there are only undulating acres of grain in the drab anonymous fields of Holderness, and then the North Sea (or German Ocean), where 'sunk St Paul's would ever show its golden cross, And still the clear water that divides us still from Norway'... Auden, yerno" (10th August 1958). This fascination, even limited as it was, seems to wear off in the later letters "ever since leaving Oxford I've worked in a library and tried to write in my spare time. For the last 16 years I've lived in the same small flat, washing in the sink, and not having central heating or double glazing or fitted carpets or the other things everyone has, and of course I haven't any biblical things such as wife, children, house, land, cattle, sheep, etc." (4th July 1972). By the last letter in the collection, his resignation is clear, "it seems strange to be such an age, and not very cheering. Presumably life has offered whatever good it's going to offer by now, and all that's left is the gloomy stuff" (9th June 1982).

That often cited Eeyore-ish side to Larkin's character is inescapable ("front door jammed. Still, it stops people getting in!" 22nd July 1974), but in these later letters to his old friend Larkin seems at his least maudlin, at ease with Iles and as devoted as he seems able to being a good friend. As Iles continued, with little success, to find a greater audience for his poetry in the 1960s and 70s, Larkin continued to offer advice, commending him to the editor of the TLS (19th April 1972) and commiserating that he seemed unable to find a publisher, "in a way you are lucky - you like your poems, and write a lot of them: perhaps you should produce them yourself, like Blake. I'm sure if Blake had sent me The Book Of Ahania I'd have told him very much what I told you." (26th February 1967). Larkin's last piece advice to Iles, in the closing paragraph of the last letter he wrote him, is to write an autobiography: "you've had an interesting life and are an original person. You could call it FUCK OFF - THIS MEANS YOU and fill it with the kind of things that used to make you roar "Argh, Christ, Kingers" in the old days" (9th June 1982).

The latest of the letters, those written after the publication of his final collection High Windows in 1974, almost all reference how Larkin has been unable to write new poems, in spite of his literary status rising to that of national monument. "I'm not really happy in the house - can't write. Only one poems this year and that a 'comic' one. Had a letter from a girl in Ramsgate saying how disgusting my poems were

Thank God she's in Ramsgate" (28th April 1975). In the penultimate letter in the collection, Larkin articulates the dilemma in full: "Well, at least you're still writing, which is more than I am. I sort of faded out in 1977. I don't mind particularly, just that I feel an awful fraud when treated as a writer, knowing I no longer am one. Kingsley seems to be able to keep going. I suppose if I didn't have anything else to do I might fake something up, but in my experience there is really no substitute for the genuine irresistible urge" (23rd July 1981).

In 2007, Iles took Larkin's advice and wrote an autobiography entitled A Way Through A War, based on his correspondence with Larkin, privately printed for circulation among close family and friends. This book reproduces all but seven letters in the archive, but most of those from the 1940s have large sections redacted and in any case the circulation of the book was so small that the letters remain essentially unpublished. Anthony Thwaite consulted a number of the letters for his Selected Letters Of Philip Larkin (Faber, 1992), publishing twenty-three of them. Again, the majority of letters from the 1940s are heavily redacted excluding in particular, details of Larkin's relationship with Philip Brown. There are twenty-five letters not published before in any meaningful way, and a further eighteen that have not been published in full.

That the correspondence essentially covers Larkin's entire adult life is most unusual. In this sense they are comparable to correspondence with only three others: Kingsley Amis (though no letters from Larkin to Amis survive for the period 1947-67); Bruce Montgomery (whom Larkin befriended in 1943 after Iles left Oxford for the army and whose letters are under seal at the Bodley until 2035); and his mother (also a forty-one years correspondence, published in November 2018). Taken in its entirety, the archive offers an extraordinary opportunity to study a large range of material that has never been meaningfully made publicly available.

From the long, vivid letters from the 1940s, providing a unique window on Larkin's formative years and showing his development as a writer both in personal and literary terms, through the composition and publication of his two published novels and his first book of verse and Larkin's increasingly refined poetic sensibilities, to the 'Larkinland' of The Whitsun Weddings and High Windows of the later letters in evidence in his descriptions of toad-like work and the gloom of ageing but equally, a ready sense of wit and irony, these letters provide a vibrant and sustained insight in to the detailed landscape of Larkin's working life.

PROVENANCE: From the estate of Norman Iles.

View details of this archive and other Larkin items in stock

Recent Posts

- The Evolution of Crime

- Tour The Bookshop On Your Screen

- The Genesis of Mr. Toad: A Short Publication History of The Wind In The Willows

- Frank Hurley's 'South'

- The "Other" Florence Harrison

- Picturing Enid Blyton

- Advent Calendar of Illustration 2020

- Depicting Jeeves and Wooster

- Evelyn Waugh Reviews Nancy Mitford

- The Envelope Booklets of T.N. Foulis

- "To Die Like English Gentlemen"

- Kay Nielsen's Fantasy World

- A Brief Look at Woodcut Illustration

- The Wealth Of Nations by Adam Smith

- What Big Stories You Have: Brothers Grimm

- Shackleton's Antarctic Career

- Inspiring Errol Le Cain's Fantasy Artwork

- Charlie & The Great Glass Elevator

- Firsts London - An Audio Tour Of Our Booth

- Jessie M. King's Poetic Art, Books & Jewellery

Blog Archive

- January 2024 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- August 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (1)

- July 2020 (2)

- March 2020 (3)

- February 2020 (2)

- October 2019 (2)

- July 2019 (2)

- May 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (2)

- February 2019 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- November 2018 (1)

- October 2018 (2)