We have just acquired a number of books from Anthony Powell’s library. Among them are some important – and surprising – presentation copies. Powell is famous for his magnum opus, the 12-volume series A Dance to the Music of Time.

Powell, who had written five novels, including Venusberg and From a View to a Death, before the war, found his inspiration for a longer series at the Wallace Collection. There he saw the form he was working towards as a writer depicted in Poussin’s painting A Dance to the Music of Time:

"The image of Time brought thoughts of mortality: of human beings facing outwards like the Seasons, moving hand in hand in intricate measure: stepping slowly, methodically, sometimes a trifle awkwardly, in evolutions that take recognizable shape: or breaking into seemingly meaningless gyrations, while partners disappear only to reappear again, once more giving pattern to the spectacle: unable to control the melody, unable, perhaps, to control the steps of the dance."

Nicholas Poussin's painting: the inspiration for A Dance to the Music of Time

Nicholas Poussin's painting: the inspiration for A Dance to the Music of Time

Powell’s view of life here, in which heroism was irrelevant but decency and humanity could still soften movements with a little grace, was not so very different from John Donne’s insight in his poem For Whom the Bell Tolls. Evelyn Waugh was undoubtedly one of the figures who wove in and out of Powell’s own life, so much so that Powell felt himself the loss after Waugh's early death in 1966: “his going,” he said, “means that a chunk of my own life has gone too.”

The association between the two writers was a strong one. Their first encounter took place at Oxford, but the friendship really took off while Powell was working at Duckworth and was on the lookout for writers in his own circle of acquaintances. In 1927, thanks to Powell, Waugh broke through to his first publishing contract, an occasion he marked with the first inscribed copy to Powell. Duckworth would retain the rights to Waugh’s travel writings, although a senior editor threw a spoke in the works and lost them Decline and Fall.

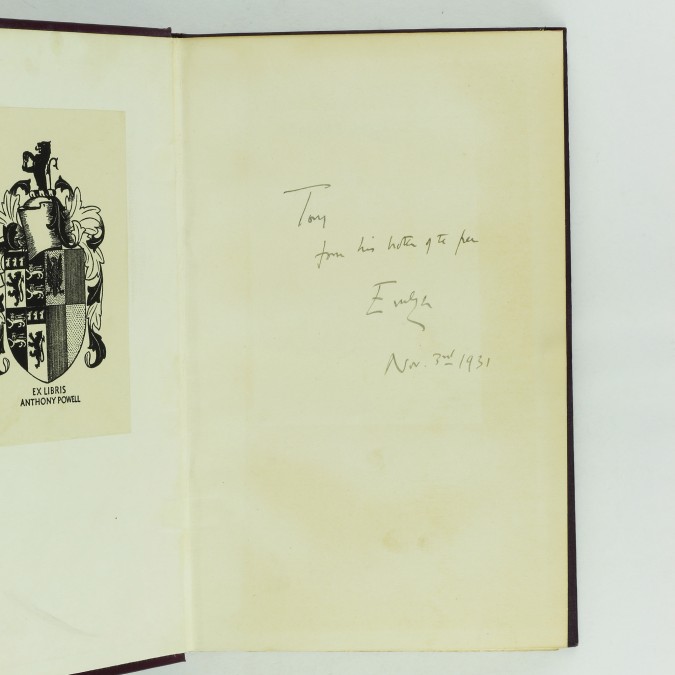

'"Tony, from his brother of the pen, Nov 3rd 1931, Evelyn": the inscription for Remote People

The breakup of Waugh’s first marriage implicated Powell’s friend John Heygate and was the cue for a temporary coldness between the two men. Unfortunately (and unwittingly) Powell was on holiday with Heygate when the news broke. Yet the authors’ shared experience and outlook on life would win out. They had in common an antipathy to social change and scepticism of anything tinged with revolutionary fervour, as well as being "brothers of the pen". Waugh, in fact, was the critic who understood so well what Powell was aiming for in Dance, that he could express it using a different metaphor altogether:

"[W]e watch through the glass of a tank; one after another various specimens swim towards us; we see them clearly, then with a barely perceptible flick of a fin or a tail they are off into the murk. That is how our encounters occur in life. Friends or acquaintances approach or recede year by year."

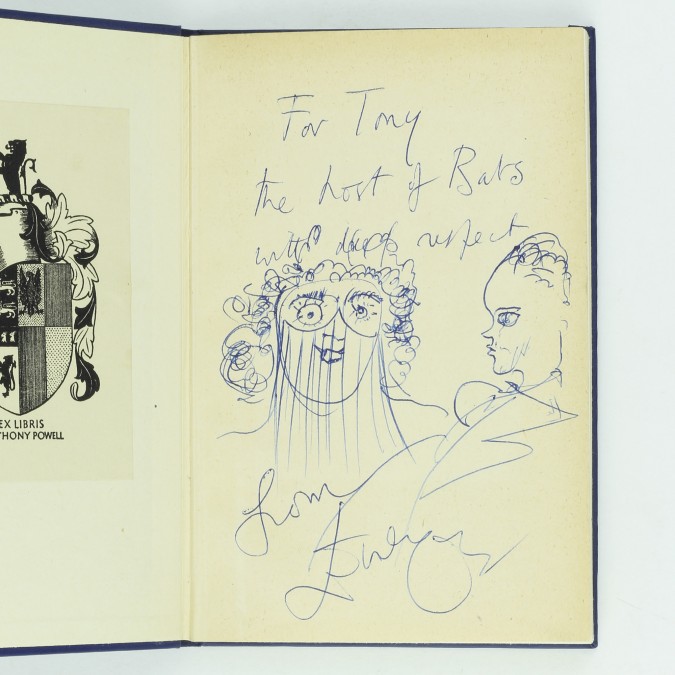

Waugh’s inscribed copies were gradually added to Powell’s library, charting the course of their friendship through moments of gratitude, admiration and fellow feeling, not to mention shamefaced apology in the form of two copies of Scott-King’s Modern Europe, the first scrawled with a cartoon drawing, and the second, presented years later, making an apology for defacement of the first.

A caricature on the first copy of Scott-King's Modern Europe

George Orwell was to be much more reticent and economical with space. His association copy is, at first glance, rather startling, yet on second thoughts bears out the point that Powell and Waugh had made with their metaphors of ritual dance and life in the aquarium. As far as overt politics went, Anthony Powell and George Orwell were poles apart. Yet as well as being writers, both were Etonians, and despite Orwell's sense of being a misfit at school and his conscious departure from the Etonian stereotype, the association counted for something. Malcolm Muggeridge, an acquaintance of Powell's, attributed their friendship to it, dryly observing that as far as his proletarian dress was concerned, "Orwell was ahead of his time; his costume is now de rigueur in public schools and universities, and is more or less the uniform of the middle- and upper-class young."

Powell admired Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, from afar, not realising what – or whom – they had in common. When Keep the Aspidistra Flying came out, he read it within days of publication and it was at this point that Cyril Connolly urged Powell to send his fellow Etonian a fan letter. Powell – perhaps with a touch of the shyness that coloured his view in those first days at school – detected a flick of the fin in Orwell’s polite, slightly distant, reply. Communication ceased.

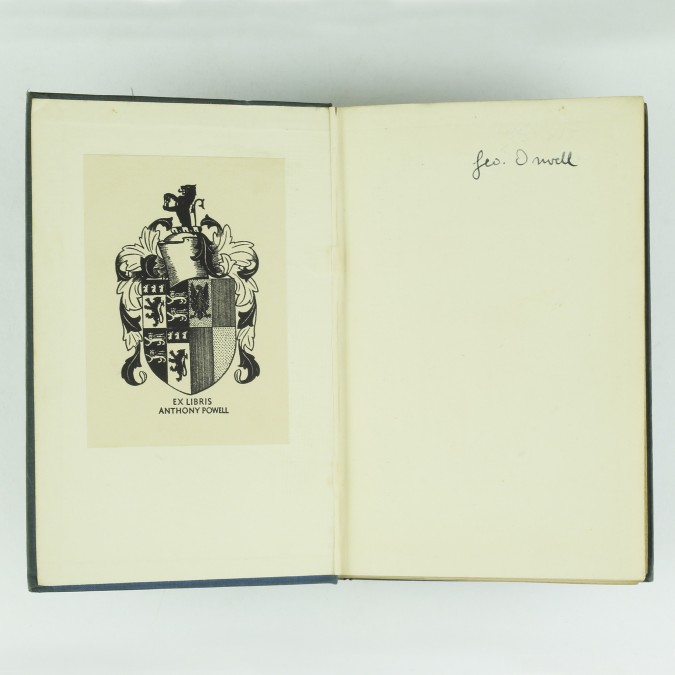

Keep the Aspidistra Flying: testament to a surprising friendship

Inevitably, however, their paths crossed once more, this time at the Café Royal in 1941. A mutual friend insisted on making the introduction, although Powell was acutely conscious of wearing his father’s blue patrols and worried these would give the wrong impression. In fact, they lit the spark of friendship: “Those straps under the feet,” said Orwell, “give you a feeling like nothing else in life.” From this point on, they corresponded until Orwell’s death in 1950 and Orwell, who so rarely inscribed his books or gave presentation copies, signed a copy of Keep the Aspidistra Flying for his friend.

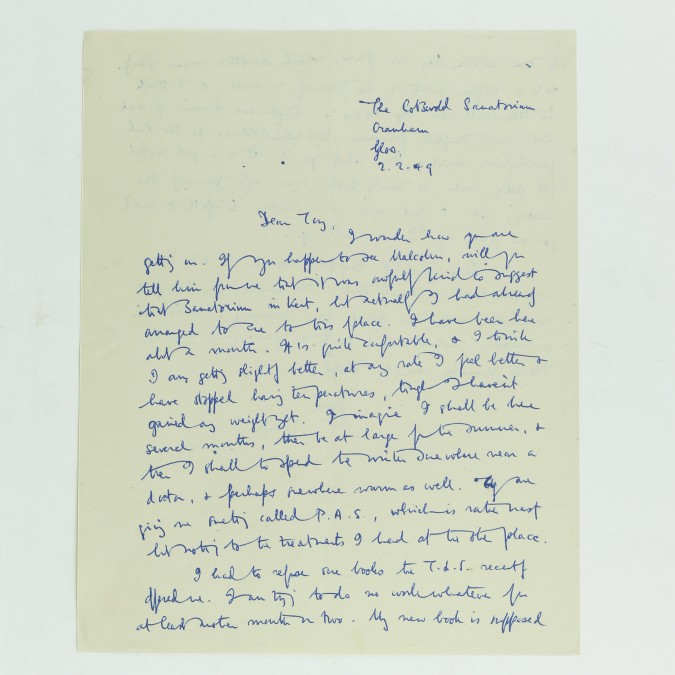

'It is a Utopia written in the form of a novel, & I think the title will be "1984"': a letter from Orwell to Powell

Powell, through Nicholas Jenkins, looked at the outward movements of his dancing characters and showed aspects of their inward lives that would have receded from view in a heroic form of narrative. Perhaps the same is true of Powell himself in relation to George Orwell: the intertwining of their lives and evidence of their connection reveals things about them that we would miss if we studied them through the lens of political allegiance. For Malcolm Muggeridge, again, the fact of the friendship pointed to an inner truth at odds with superficial appearances:

"Orwell’s politics and general view of life were curiously confused, and sometimes seemingly contradictory. In principle, he was a Socialist with left-wing leanings…Actually, many of his views were strongly, even pathologically conservative, more so than Tony’s."

Michael Barber suggests that Orwell’s theories about power and its attractions helped to shape the Dance. If so, then for both authors, the things and the way that they wrote surely shaped them in turn and enabled them to surprise each other by transforming acquaintance into strong friendship. As Orwell was to put it, Powell was “the only Tory I have ever liked”, while for Powell who “never much cared for people who wanted to set the world to rights,” Orwell was, “someone for whom it was impossible not to feel a deep affection.”

For association copies and other items from Anthony Powell’s library click here.

Recent Posts

- The Evolution of Crime

- Tour The Bookshop On Your Screen

- The Genesis of Mr. Toad: A Short Publication History of The Wind In The Willows

- Frank Hurley's 'South'

- The "Other" Florence Harrison

- Picturing Enid Blyton

- Advent Calendar of Illustration 2020

- Depicting Jeeves and Wooster

- Evelyn Waugh Reviews Nancy Mitford

- The Envelope Booklets of T.N. Foulis

- "To Die Like English Gentlemen"

- Kay Nielsen's Fantasy World

- A Brief Look at Woodcut Illustration

- The Wealth Of Nations by Adam Smith

- What Big Stories You Have: Brothers Grimm

- Shackleton's Antarctic Career

- Inspiring Errol Le Cain's Fantasy Artwork

- Charlie & The Great Glass Elevator

- Firsts London - An Audio Tour Of Our Booth

- Jessie M. King's Poetic Art, Books & Jewellery

Blog Archive

- January 2024 (1)

- January 2023 (1)

- August 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (1)

- July 2020 (2)

- March 2020 (3)

- February 2020 (2)

- October 2019 (2)

- July 2019 (2)

- May 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (2)

- February 2019 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- November 2018 (1)

- October 2018 (2)